America’s Sacrifice

This section contains writings that highlight the sacrifices Americans are willing to make yesterday, today and tomorrow in defense of freedom and liberty.

Lt. Brian Bradshaw

Washington Post

July 15, 2009

Pg. 19

A Soldier Comes Home

On July 5, The Post published a letter from Martha Gillis of Springfield, whose nephew, Lt. Brian Bradshaw, was killed in Afghanistan on June 25, the day that Michael Jackson died. The letter criticized the extensive media coverage of Jackson’s death compared with the brief coverage of Lt. Bradshaw’s death. Among the responses was the following letter, written July 9 by an Air National Guard pilot and a fellow member of the crew that flew Lt. Bradshaw’s body from a forward base in Afghanistan to Bagram Air Base. Capt. James Adair, one of the plane’s pilots, asked the editorial page staff to forward the letter to the Bradshaw family. He and Brian Bradshaw’s parents then agreed to publication of these excerpts.

Dear Bradshaw Family,

We were crew members on the C-130 that flew in to pick up Lt. Brian Bradshaw after he was killed. We are Georgia Air National Guardsmen deployed to Afghanistan for Operation Enduring Freedom. We support the front-line troops by flying them food, water, fuel, ammunition and just about anything they need to fight. On occasion we have the privilege to begin the final journey home for our fallen troops. Below are the details to the best of our memory about what happened after Brian’s death.

We landed using night-vision goggles. Because of the blackout conditions, it seemed as if it was the darkest part of the night. As we turned off the runway to position our plane, we saw what appeared to be hundreds of soldiers from Brian’s company standing in formation in the darkness. Once we were parked, members of his unit asked us to shut down our engines. This is not normal operating procedure for that location. We are to keep the aircraft’s power on in case of maintenance or concerns about the hostile environment. The plane has an extremely loud self-contained power unit. Again, we were asked whether there was any way to turn that off for the ceremony that was going to take place. We readily complied after one of our crew members was able to find a power cart nearby. Another aircraft that landed after us was asked to do the same. We were able to shut down and keep lighting in the back of the aircraft, which was the only light in the surrounding area. We configured the back of the plane to receive Brian and hurried off to stand in the formation as he was carried aboard.

Brian’s whole company had marched to the site with their colors flying prior to our arrival. His platoon lined both sides of our aircraft’s ramp while the rest were standing behind them. As the ambulance approached, the formation was called to attention. As Brian passed the formation, members shouted “Present arms” and everyone saluted. The salute was held until he was placed inside the aircraft and then the senior commanders, the sergeant major and the chaplain spoke a few words.

Afterward, we prepared to take off and head back to our base. His death was so sudden that there was no time to complete the paperwork needed to transfer him. We were only given his name, Lt. Brian Bradshaw. With that we accepted the transfer. Members of Brian’s unit approached us and thanked us for coming to get him and helping with the ceremony. They explained what happened and how much his loss was felt. Everyone we talked to spoke well of him — his character, his accomplishments and how well they liked him. Before closing up the back of the aircraft, one of Brian’s men, with tears running down his face, said, “That’s my platoon leader, please take care of him.”

We taxied back on the runway, and, as we began rolling for takeoff, I looked to my right. Brian’s platoon had not moved from where they were standing in the darkness. As we rolled past, his men saluted him one more time; their way to honor him one last time as best they could. We will never forget this.

We completed the short flight back to Bagram Air Base. After landing, we began to gather our things. As they carried Brian to the waiting vehicle, the people in the area, unaware of our mission, stopped what they were doing and snapped to attention. Those of us on the aircraft did the same. Four soldiers who had flown back with us lined the ramp once again and saluted as he passed by. We went back to post-flight duties only after he was driven out of sight.

Later that day, there was another ceremony. It was Bagram’s way to pay tribute. Senior leadership and other personnel from all branches lined the path that Brian was to take to be placed on the airplane flying him out of Afghanistan. A detail of soldiers, with their weapons, lined either side of the ramp just as his platoon did hours before. A band played as he was carried past the formation and onto the waiting aircraft. Again, men and women stood at attention and saluted as Brian passed by. Another service was performed after he was placed on the aircraft.

For one brief moment, the war stopped to honor Lt. Brian Bradshaw. This is the case for all of the fallen in Afghanistan. It is our way of recognizing the sacrifice and loss of our brothers and sisters in arms. Though there may not have been any media coverage, Brian’s death did not go unnoticed. You are not alone with your grief. We mourn Brian’s loss and celebrate his life with you. Brian is a true hero, and he will not be forgotten by those who served with him.

We hope knowing the events that happened after Brian’s death can provide you some comfort.

Sincerely,

Capt. James Adair

Master Sgt. Paul Riley

GA ANG 774 EAS Deployed

Classification: UNCLASSIFIED

Caveats: NONE

Sergeant Alvin York on Liberty and Freedom

Sergeant Alvin York, Medal of Honor recipient and much decorated hero of the First World War said this of defending liberty and freedom:

“Liberty and freedom and democracy are so very precious that you do not fight to win them once and stop. You do not do that. Liberty and freedom and democracy are prizes awarded only to those peoples who fight to win them and then keep fighting eternally to hold them.”

The Death of Captain Waskow

This is the most famous and most widely-reprinted column by Ernie Pyle.

AT THE FRONT LINES IN ITALY, January 10, 1944 – In this war I have known a lot of officers who were loved and respected by the soldiers under them. But never have I crossed the trail of any man as beloved as Capt. Henry T. Waskow of Belton, Texas.

Capt. Waskow was a company commander in the 36th Division. He had led his company since long before it left the States. He was very young, only in his middle twenties, but he carried in him a sincerity and gentleness that made people want to be guided by him.

“After my own father, he came next,” a sergeant told me.

“He always looked after us,” a soldier said. “He’d go to bat for us every time.”

“I’ve never knowed him to do anything unfair,” another one said.

I was at the foot of the mule trail the night they brought Capt. Waskow’s body down. The moon was nearly full at the time, and you could see far up the trail, and even part way across the valley below. Soldiers made shadows in the moonlight as they walked.

Dead men had been coming down the mountain all evening, lashed onto the backs of mules. They came lying belly-down across the wooden pack-saddles, their heads hanging down on the left side of the mule, their stiffened legs sticking out awkwardly from the other side, bobbing up and down as the mule walked.

The Italian mule-skinners were afraid to walk beside dead men, so Americans had to lead the mules down that night. Even the Americans were reluctant to unlash and lift off the bodies at the bottom, so an officer had to do it himself, and ask others to help.

The first one came early in the morning. They slid him down from the mule and stood him on his feet for a moment, while they got a new grip. In the half light he might have been merely a sick man standing there, leaning on the others. Then they laid him on the ground in the shadow of the low stone wall alongside the road.

I don’t know who that first one was. You feel small in the presence of dead men, and ashamed at being alive, and you don’t ask silly questions.

We left him there beside the road, that first one, and we all went back into the cowshed and sat on water cans or lay on the straw, waiting for the next batch of mules.

Somebody said the dead soldier had been dead for four days, and then nobody said anything more about it. We talked soldier talk for an hour or more. The dead man lay all alone outside in the shadow of the low stone wall.

Then a soldier came into the cowshed and said there were some more bodies outside. We went out into the road. Four mules stood there, in the moonlight, in the road where the trail came down off the mountain. The soldiers who led them stood there waiting. “This one is Captain Waskow,” one of them said quietly.

Two men unlashed his body from the mule and lifted it off and laid it in the shadow beside the low stone wall. Other men took the other bodies off. Finally there were five lying end to end in a long row, alongside the road. You don’t cover up dead men in the combat zone. They just lie there in the shadows until somebody else comes after them.

The unburdened mules moved off to their olive orchard. The men in the road seemed reluctant to leave. They stood around, and gradually one by one I could sense them moving close to Capt. Waskow’s body. Not so much to look, I think, as to say something in finality to him, and to themselves. I stood close by and I could hear.

One soldier came and looked down, and he said out loud, “God damn it.” That’s all he said, and then he walked away. Another one came. He said, “God damn it to hell anyway.” He looked down for a few last moments, and then he turned and left.

Another man came; I think he was an officer. It was hard to tell officers from men in the half light, for all were bearded and grimy dirty. The man looked down into the dead captain’s face, and then he spoke directly to him, as though he were alive. He said: “I’m sorry, old man.”

Then a soldier came and stood beside the officer, and bent over, and he too spoke to his dead captain, not in a whisper but awfully tenderly, and he said:

“I sure am sorry, sir.”

Then the first man squatted down, and he reached down and took the dead hand, and he sat there for a full five minutes, holding the dead hand in his own and looking intently into the dead face, and he never uttered a sound all the time he sat there.

And finally he put the hand down, and then reached up and gently straightened the points of the captain’s shirt collar, and then he sort of rearranged the tattered edges of his uniform around the wound. And then he got up and walked away down the road in the moonlight, all alone.

After that the rest of us went back into the cowshed, leaving the five dead men lying in a line, end to end, in the shadow of the low stone wall. We lay down on the straw in the cowshed, and pretty soon we were all asleep.

Source: Ernie’s War: The Best of Ernie Pyle’s World War II Dispatches, edited by David Nichols, pp. 195-97. Pictures courtesy of The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.

Thoughts from the Revolutionary War

Lt. James McMichael of America’s First Army, the Revolutionary War Army, like all soldiers, feared death. They all knew that their lives could end at any moment on the battlefield, that they could fall from a musket ball or bayonet. It was the fear that soldiers carried within their hearts for centuries and would continue to carry long after the Revolution. During the blackest hours of the rebellion, McMichael ever apprehensive about his safety, wrote a poem about being killed, such as one he finished the night before a battle;

When I lay down I thought and said Perhaps tomorrow I may be dead Yes I shall stand with all my might And for sweet liberty will fight.

Selected quotes from “The First American Army” by Bruce Chadwick

Copyright 2005 by Bruce Chadwick

Reprinted by permission of Sourcebooks, Inc

Perhaps Lt. Jeremiah Greenman’s post-war life was representative of most of the unheralded soldiers who fought in the first American army. Greenman, shot twice during the Revolution, had no skills when he entered the army at age seventeen and despite some experience as a regimental clerk, had none when he left on the day the army took possession of New York City in 1783. He drifted for a few years after he returned to Providence and then worked as a sea captain from 1790 to 1805, but never really enjoyed it. Then, with his family, he moved to Marietta, Ohio in 1806 to run a farm. He died there in 1828 at the age of seventy-one. On his tombstone his sons carved an inscription that might have served for all the soldiers in the first American army: “Revolutionary Soldier-in memory of Jeremiah Greenman Esq an active officer in the army which bid defiance to britons power and established the independence of the United States.”

Selected quotes from “The First American Army” by Bruce Chadwick

Copyright 2005 by Bruce Chadwick

Reprinted by permission of Sourcebooks, Inc.

Abraham Lincoln’s letter to Lydia Bixby

In November of 1864 President Abraham Lincoln was informed that Lydia Bixby, a Boston widow, had lost five sons in the Civil War. Below is a copy of the moving letter of condolence that President Lincoln wrote to her.

Executive Mansion

Washington, Nov. 21, 1864

To Mrs. Bixby, Boston, Mass.

Dear Madam,

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts, that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle.

I feel how weak and fruitless must be any words of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering to you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic they died to save.

I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours, to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of Freedom.

Yours very sincerely and respectfully,

Abraham Lincoln

Major John Alexander Hotell III

A Soldier’s Own Obituary

Major John Alexander Hottell, III graduated from West Point in 1964, tenth in a class of 564. He was a Rhodes scholar in 1965. In Vietnam he earned two Silver Stars as a company commander. He later became aide to the First Cavalry Division commander, Major General George W. Casey. Both were killed in the crash of a helicopter on July 7, 1970. He was 27 years old at the time of his death, which occurred about one year after he wrote his own obituary and sent it in a sealed envelope to his wife, Linda. It was published in The New York Times and reads as follows:

“I am writing my own obituary for several reasons, and I hope none of them are too trite. First, I would like to spare my friends, who may happen to read this, the usual clichés about being a good soldier. They were all kind enough to me, and I not enough to them. Second, I would not want to be a party to perpetuation of an image that is harmful and inaccurate; “glory” is the most meaningless of concepts, and I feel that in some cases it is doubly damaging. And third, I am quite simply the last authority on my own death. “I loved the Army; it reared me, it nurtured me, and it gave me the most satisfying years of my life. Thanks to it I have lived an entire lifetime in 26 years. It is only fitting that I should die in its service. We all have but one death to spend, and insofar as it can have any meaning, it finds it in the service of comrades in arms. “And yet, I deny that I died FOR anything – not my country, not my Army, not my fellow man, none of these things. I LIVED for these things, and the manner in which I chose to do it involved the very real chance that I would die in the execution of my duties. I knew this, and accepted it, but my love for West Point and the Army was great enough – and the promise that I would some day be able to serve all the ideals that meant anything to me through it was great enough – for me to accept this possibility as a part of a price which must be paid for all things of great value. If there is nothing worth dying for – in this sense – there is nothing worth living for. “The Army let me live in Japan, Germany and England with experiences in all of these places that others only dream about. I have skied in the Alps, killed a scorpion in my tent camping in Turkey, climbed Mount Fuji, visited the ruins of Athens, Ephesus and Rome, seen the town of Gordium where another Alexander challenged his destiny, gone to the opera in Munich, plays in the West End of London, seen the Oxford-Cambridge rugby match, gone for pub crawls through the Cotswolds, seen the night-life in Hamburg, danced to the Rolling Stones, and earned a master’s degree in a foreign university. “I have known what it is like to be married to a fine and wonderful woman and to love her beyond bearing with the sure knowledge that she loves me; I have commanded a company and been a father, priest, income-tax adviser, confessor, and judge for 200 men at one time; I have played college football and rugby, won the British national diving championship two years in a row, boxed for Oxford against Cambridge only to be knocked out in the first round, and played handball to distraction – and all of these sports I loved, I learned at West Point. They gave me hours of intense happiness. “I have been an exchange student at the German Military Academy, and gone to the German Jumpmaster school. I have made thirty parachute jumps from everything from a balloon in England to a jet at Fort Bragg. I have written an article that was published in Army magazine, and I have studied philosophy. “I have experienced all these things because I was in the Army and because I was an Army brat. The Army is my life, it is such a part of what I was that what happened is the logical outcome of the life I loved. I never knew what it is to fail. I never knew what it is to be too old or too tired to do anything. I lived a full life in the Army, and it has exacted the price. It is only just.”

Address at the Dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg. November 19, 1863

Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth upon this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But in a larger sense we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us; that from these honoured dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion; that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain; that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom; and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

President Abraham Lincoln

Remember Pearl Harbor

The USS Arizona commissioned on October 17, 1916 was sunk on December 7, 1941, “a day of infamy”, at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Many of the 1,177 of the battleship’s lost crew are still entombed in its sunken hull.

The USS Arizona Memorial, dedicated on Memorial Day 1962, spans the mid-portion of the sunken Arizona. In memory and honor of all the American servicemen who gave the ultimate sacrifice for their country, the American Flag is flown daily over the USS Arizona Memorial.

A bronze plaque at the foot of the flagpole reads:

DEDICATED TO THE ETERNAL MEMORY OF OUR GALLANT SHIPMATES IN THE USS ARIZONA WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES IN ACTION 7 DECEMBER 1941

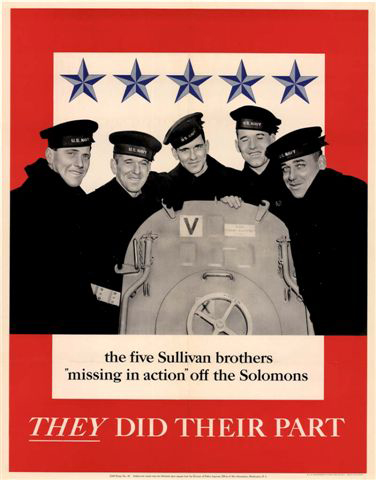

Navy Department Press Release of February 2, 1943

The following letter was sent to Mrs. Sullivan by President Roosevelt when he learned that her five sons were listed as missing in action after the USS Juneau was sunk:

Dear Mrs. Sullivan:

The knowledge that your five gallant sons are missing in action, against the enemy, inspired me to write you this personal message. I realize full well there is little I can say to assuage your grief.

As the Commander in Chief of the Army and the Navy, I want you to know that the entire nation shares your sorrow. I offer you the condolence and gratitude of our country. We, who remain to carry on the fight, must maintain the spirit in the knowledge that such sacrifice is not in vain. The Navy Department has in-

formed me of the expressed desire of your sons; George Thomas, Francis Henry, Joseph Eugene, Madison Abel, and Albert Leo, to serve on the same ship. I am sure, that we all take pride in the knowledge that they fought side by side. As one of your sons wrote, `We will make a team together that can’t be beat.’ It is

this spirit which in the end must triumph.

Last March, you, Mrs. Sullivan, were designated to sponsor a ship of the Navy in recognition of your patriotism and that of your sons. I am to understand that you are, now, even more determined to carry on as sponsorer. This evidence of unselfish-

ness and courage serves as a real inspiration for me, as I am sure it will for all Americans. Such acts of fate and fortitude in the face of tragedy convince me of the indomitable spirit and will of our people.

I send you my deepest sympathy in your hour of trial and pray that in Almighty God you will find a comfort and help that only He can bring.

Very sincerely yours,

Franklin D. Roosevelt

The Bedford Boys

One American town’s ultimate D-Day Sacrifice

June 6, 1944: Nineteen boys from rural Bedford, Virginia, died in the first bloody minutes of D-Day. They were part of Company A of the 116th Regiment of the 29th Division and among the first wave of American soldiers to hit the beaches at Normandy. Later in the campaign, three more boys from this small Virginia community died of gunshot wounds. Bedford was a tight-knit community of three thousand before the war whose English ancestors had settled the area in the 1700’s. In the 1930’s the young men of Bedford joined the National Guard for extra dollars during the depression. Many of them would still be in Company A on D-Day. The following is a list of those who made the ultimate sacrifice at Normandy.

Twenty-two Bedford boys were killed in action:

- Leslie Abbott

- Walace Carter

- John Clifton

- John Dean

- Frank Draper Jr.

- Taylor Fellers

- Charles Fizer

- Nicholas Gillaspie

- Bedford Hoback

- Raymond Hoback

- Clifton Lee

- Earl Parker

- Joseph Parker

- Jack Powers

- Weldon Rosazza

- John Reynolds

- John Schenk

- Ray Stevens

- Gordon White

- John Wilkes

- Elmere Wright

- Grant Yopp

The entire 116th Infantry Regiment suffered 797 casualties, including 375 killed or missing in action. The 116th received a Distinguished Unit Citation for “Extraordinary heroism and outstanding performance of duty in action in the initial assault on the northern coast of Normandy France.”

Eleven of Bedford’s sons lie in the American cemetery at Colleville sur Mer a few hundred yards from the beach where they died, beside 9,386 other American dead from the battle for Normandy. In a chapel at the heart of the rows of dead, each with a cross pointing west-towards home-the following words are in scribed for all to see:

“Think not only upon their passing. Remember the glory of their spirit.”

Selected quotes from THE BEDFORD BOYS by Alex Kershaw

Copyright 2003 by Alex Kershaw

Reprinted by permission of Da Capo, a member of Perseus Books, L.L.C.

Memorial Day 1942

Houston, Texas

On March 1, 1942 the USS Houston (CA-30), Heavy Cruiser was sunk by the Japanese off of Sunda Strait in the Pacific. It was the first American capital ship sunk in the Pacific after war was declared. Shortly thereafter the Navy Department announced a new cruiser named Houston (CL-81) would be launched in June 1943. On Memorial Day 1942 the city of Houston asked for 1000 “Houston Volunteers” to man the new cruiser, over three thousand answered the call. President Roosevelt sent a letter to all in attendance that day commemorating their effort. Below is a copy of that letter.

On this Memorial Day, all America joins with you who are gathered in proud tribute to a great ship and a gallant company of American officers and men. That fighting ship and those fighting Americans shall live forever in our hearts.

I knew that ship and loved her. Her officers and men were my friends.

When ship and men went down, still fighting, they did not go down to defeat. They had helped remove at least two cruisers and probably other vessels from the active list of the enemy’s rank. The officers and men of the U.S.S Houston were privileged to prove, once again, that free Americans consider no price too high to pay in defense of their freedom. The officers and men of the U.S.S Houston drove a hard bargain. They sold their liberty and their lives most dearly.

The spirit of these officers and men is still alive. That is being proved today in all Houston, in all Texas, in all America. Not one of us doubts that the thousand recruits sworn in today will carry on with the same determined spirit shown by the gallant men who have gone before them. Not one of us doubts that every true Texan and every true American will back up these new fighting men, and all our fighting men, with all our hearts and all our efforts.

Our enemies have given us the chance to prove that there will be another U.S.S Houston, and yet another U.S.S Houston if that becomes necessary, and still another U.S.S Houston as long as American ideals are in jeopardy. Our enemies have given us the chance to prove that an attack on peace-loving but proud Americans is the very gravest of all mistakes.

The officers and men of the U.S.S Houston have placed us all in their debt by winning a part of the victory which is our common goal. Reverently, and with humility, we acknowledge this debt. To those officers and men, wherever they may be, we give our solemn pledge that the debt will be repaid in full.

Franklin D. Roosevelt